Tara Reade and the Mask-Off Moment For MeToo's Moneyed Advocates

The corporate interests that pushed a social movement against sexual misconduct abandoned its principles once they required any meaningful conviction

I waited with great interest in the weeks that followed March 25, the day when Tara Reade appeared on Katie Halper’s podcast and accused Joe Biden of sexual assault, for how the matter would be handled by the liberal corporate media apparatus.

In the interest of full disclosure, I supported Bernie Sanders in the Democratic primary. As someone who had dubious accusations weaponized against him by the media without vetting, I wasn’t interested in immediately cancelling Biden without a review of the facts, no matter how helpful it would have been to the candidate I supported. Given how press coverage to Sanders was often unfairly dismissive or outright dishonest, however, I was at least curious how the media would frame a potentially disqualifying claim made against the party’s frontrunner.

To watch over the last few years how prominent writers and media outlets have summarily granted any accusation of sexual misconduct complete credibility, occasionally without investigation, and campaign for the destruction of the lives of the accused, it is - I say without exaggeration - traumatizing to see them perform an about-face when the accused happens to be a powerful politician with the inside track on the nomination and the support of corporate interests.

In the first week or so following Reade’s interview, a handful of notable publications - many conservative, a few aligned with liberal interests like Vox and Salon - acknowledged the allegation of sexual assault, though the liberal ones took pains to stress the complexity of the situation and discuss it in dry, matter-of-fact tones. Typically, at least since the dawn of MeToo, these publications were quick to dramatize allegations, play them up for maximum sympathy, and presume victimhood on the part of the accuser.

A useful example on how allegations are typically framed is a recent story from The Huffington Post on how Covid-19 delayed the arbitration of Title IX complaints on college campuses. In the article, without any investigation into the accusations, those who have filed the complaints are referred to as “survivors” by default. It’s quite possible these women have survived assault or other forms of trauma, but no effort had yet been made to determine that. Nevertheless, HuffPo reflexively grants them permanent victim status. That’s a politicized way of approaching the matter, one that has been the norm across the board by liberal outlets in recent years. At least in this case the accused aren’t named, but often the media hasn’t been any more careful when they have been.

Meanwhile, The New York Times and The Washington Post, the supposed leading lights of the mainstream media, were silent about Reade until this past Sunday. How these outlets ended up framing the story mattered a great deal, and would likely dictate how many others, print and broadcast, handled it as well. Already it should be noted that the deliberate care shown by corporate journalists in this instance far exceeded the norm during the MeToo era. Conservatives have been eager to point out the contradictions between this allegation and the ones made against Brett Kavanaugh in 2018, understandably so, though it should be acknowledged that even with all the scandal the press created, he was still confirmed by Republicans to the Supreme Court. At the time, I objected to how Republicans rushed the confirmation process to prevent a more thorough investigation, but it’s clear the Democrats and the media were operating in bad faith as well.

The Times, for instance, publicized the allegation made by Christine Blasey Ford against Brett Kavanaugh before her name was attached to it and before she gave approval to have the allegation publicized. The Times wrote an article in September 2018 about a “secretive letter” being shared among senate Democrats that mentioned an allegation of attempted assault by Kavanaugh from when he was a teenager. Whereas the Times insisted it was doing the responsible thing by not covering Reade without talking to her, the paper wrote about the secret letter without reporters viewing it. A few days later, Ford was essentially coaxed into the public eye to present the case on her terms. For Reade, it took weeks following her explicitly going on the record and extensive investigation by The Times and The Post to cover the allegation, coverage that was framed from a perspective of clear skepticism.

NYT Executive Editor Dean Banquet, in an interview with his paper’s media columnist on Monday, maintained the coverage of Ford and Reade followed the same standard. According to him, the reason Kavanaugh got more sweeping and dramatic coverage was because it was already a “running, hot” story. What Banquet doesn’t bother to mention is NYT’s role in manufacturing Ford’s allegation into a hot story, even before Ford gave her blessing for it to be publicized. In fact, according to that first NYT article about the letter in September 2018, Ford, then still anonymous, asked Sen. Dianne Feinstein not to publicize it. It’s not clear who alerted the press, but it stands to reason that prominent Democrats saw this as a potential attack, first and foremost.

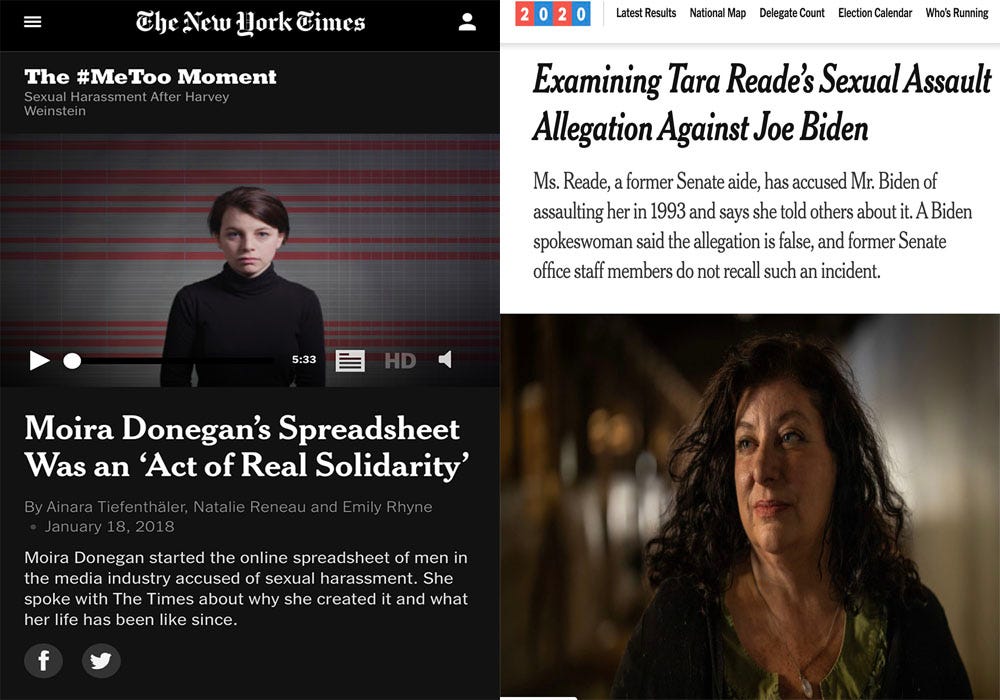

This ordeal hits close to home as NYT was one of several prominent outlets that publicized the Shitty Media Men list, a crowdsourced spreadsheet of anonymous allegations ranging from rape to “awkward in the DMs”, most of which were never investigated, yet weaponized and promoted all the same. The Times may not have printed the contents of the list. By covering it without extensive fact-checking, however, they were essentially endorsing a document that was publicly available online.

In January 2018, the Times produced a video interview with Moira Donegan about her creating the spreadsheet and dealing with its fallout. It was a work of veneration. The video accompanies a longer article about the list, with only one anonymous quote from a man named on it regarding how men inaccurately accused might be too petrified to come forward, but that hardly had the emotional oomph of Donegan fighting off tears on camera. The headline for the video package cites her words, describing the list as “an act of solidarity,” an unblemished positive. Whatever you think of the overall impact of the list, it’s a little curious that the woman who claimed the list was never supposed to go public was soaking in the publicity associated with it now that it was out for all to see.

That might be fine if there was any attempt to reckon with the negatives of it. There hasn’t been. This past January, when I broke my silence and finally addressed in an essay what was claimed about me, its unfairness, and the damage it caused, Donegan immediately blocked me on Twitter. She hasn’t acknowledged what I wrote in any way in the months since. No one from the writing community that took part in creating, disseminating, and weaponizing the list has said anything publicly.

I pitched the piece to a handful of liberal outlets, receiving vague dismissals from editors who were at the same time confident that some other place surely would pick it up. Eventually I decided to self-publish on Medium. It had been a long enough process for me and the daily psychological torture was such that I had to get my story out there, for my own mental well-being more than anything. A couple conservative outlets amplified it, and I wonder about the purity of their motives but when I saw no room for debate among Democrats, it was my only option aside from stewing in my frustration, potentially for years longer. The New York Post agreed to republish a slightly condensed version of the piece. Quillette, a mostly right-wing online magazine that has published numerous articles critical of MeToo’s perceived overreaches, wrote about my case as well.

Some conservatives and MeToo critics objected to my disagreement with pursuing legal action against Donegan and what they saw as me defending the tactics of an anonymously compiled, largely unvetted allegations. I made clear in that essay that I think such a document is anti-journalistic and shouldn’t be supported by any community interested in fact-checking and fairness. My lack of aggressive language was informed by a faith that the journalistic community might reckon with what was done. That faith was clearly misplaced, because that hasn’t happened at all. Instead, it was roundly ignored by liberal writers and outlets.

Months later, I’m more ambivalent about Stephen Elliott’s lawsuit. He told me that after he filed the suit a few copycat versions of the list were shut down on college campuses. Given how little effort has been made to uncover the truth behind anonymous claims in a professional setting where investigations are supposed to be part of the job description, I can’t imagine universities going any further to check facts, especially when purging people regardless of actual guilt can be a solid PR move in a climate where the public wants a sense of accountability on sexual misconduct, real or perceived.

What’s more, Donegan’s callous opportunism has not been reined in or challenged by her peers. Just a few months ago, she was celebrated again as a hero in a VICE profile. Since publishing my story, I spoke with another man named on the list who has yet to come forward with his story, and he told me that he reached out to Donegan through a lawyer to reach a non-legal resolution in an attempt to find out who made claims against him that he calls baseless. Donegan completely ignored him. She has been glad to turn other people’s trauma into professional gain, but there’s no effort to hold her accountable for any of the negatives of the list, or suggest that there was collateral damage caused by her reckless tactics.

The larger problem with cancelling individuals for vague unproven charges, beyond even the possibility of convicting the innocent, is that the societal issue of sexual misconduct was too pervasive to punish everyone who has trespassed. Certainly the Shitty Media Men list didn’t come close to catching everyone it could have caught in media. That’s because the ability to add allegations to the spreadsheet was only open to those connected to very privileged segments of NYC media circles. I don’t live in New York and my connections to those powerful professional circles are fairly limited, but it’s clear someone within them doesn’t like me enough that they invented damaging claims that were indisputably intended to destroy my life. It’s very easy, and certainly convenient, for an industry to get behind one poorly guarded - possibly by design - anonymous spreadsheet, publicize it, wipe their hands, and say the industry has gotten rid of all of its bad apples.

What’s more, if a man has done something wrong, there’s little incentive for him to change. At worst, he’s been kicked out of a socioeconomic class and now working class women have to deal with him. One of the more common criticisms of MeToo is that its mechanisms were almost exclusively available to wealthy and occasionally middle-class women. When men are driven from their profession, where are they to go except more precarious work with more precarious people? Since cancellation never has an established endpoint and no attempt at rehabilitation is made, even assuming a man did what was alleged of him, what reason is there to get better aside from public humiliation?

The professional class activists who leveraged MeToo into greater prominence and success - Donegan, Alyssa Milano, Amanda Marcotte, Jill Filipovic, writers at Jezebel, among others - have suddenly stressed the need for responsibility and due process now that the person accused is the presumptive Democratic nominee for president. This stands in stark contrast to how they framed allegations against men who were not so critical to upholding their class status and political interests.

Milano especially has come under fire for her transparent cynicism, from expressing zero tolerance for alleged sexual predators in office in 2017 when it was Al Franken to sudden pleas for thorough investigation and due process when it’s Joe Biden facing an allegation in 2020. Aside from Franken, her targets primarily were Republicans over the last few years. But now that it’s the Democratic frontrunner, who happens to not be calling for substantive economic reforms that might alienate rich celebrities, it’s time to call off the cancel mob.

Rose McGowan, another actress who played a central role in Hollywood’s grappling with MeToo, in a 2018 interview with ABC News called out Milano’s connection with CAA. She has accused the talent agency of enabling Weinstein by arranging private meetings with actresses during the years when he was able to lord over the industry. McGowan famously described CAA’s partnership with Times Up as a PR move to avoid confronting their complicity in the abuse over the years. Times Up has come under scrutiny in recent weeks for their connection to the Biden campaign while declining to provide assistance to Tara Reade because she isn’t pursuing a court case.

It’s clear now MeToo was amplified as a cultural phenomenon both because it was a necessary societal reckoning, but also because big industries saw in it a crisis that could implicate them, so there had to be a visible campaign to, yes, unmask serious predators, but also rope in a few scapegoats to serve as examples, in a haphazard way free of any coherent process. There’s a little bit of everything - some justice, some opportunism, some cruelty, a great deal of confusion. That’s all incidental so long as the companies can claim something was done and get back to the business at hand.

In the fall of 2018, shortly after Elliott filed his lawsuit against Donegan, who is being represented by Times Up co-founder Roberta Kaplan, The Cut anonymously interviewed five of the men named on the list. I wasn’t among them, though an answer from one of them stuck with me:

I didn’t do what I’m accused of on the list. But obviously I wronged somebody to the point that they want to mess with my life. To this day I don’t know what that was. I just think, the list is out there. I need to move on. It’s taking one for the team.

I understand both the desire to move on and to “take one for the team.” I think that’s partially why I didn’t want to sue Donegan. I would be interested in knowing whether he was one of the men included on the list who was protected from career ruin by being a full-time staff writer, and therefore could share his side with an employer. As a freelancer, I didn’t have that luxury. I was roundly judged and cut off. In a weird way, being implicated made me want the Shitty Media Men list to have been a worthy project. I don’t think most people who participated and supported it had malicious intent, even if it hurt some people it shouldn’t have and was likely way harsher than it should have been in other cases. It was comforting to believe if I had to be treated unfairly, at least it was in service of a higher purpose.

You could argue I’m not doing either of those things anymore, but I wonder — what is the team, exactly? Members of the media? Almost none of them were concerned about whether my accusations were true, and some cut me off without asking. Is the team a stand-in for a vague set of progressive values? Perhaps. How do I accept that as a coherent belief system when the liberal center-left is currently dismissing an on-the-record allegation of rape after four years of loudly demonstrating against the evils of a predator in the White House?

The team I fought for is no longer in the race. I don’t see any team left that has my back.